“They always say the best way to see the Gwent Levels is with a microscope or a helicopter.” I was walking through the stunning June meadows and dense willow copses of Magor Marsh Nature Reserve with Sorrel Jones, a conservation officer for the Gwent Wildlife Trust. The last relic fenland in south-east Wales, Magor Marsh was my first port of call on the protected Levels, and it hadn’t taken long to understand its significance – the place thrummed and buzzed with summer life. “You’ve either got to get right in and go, Look, this is amazing down here, or you’ve got to get up high and see this vast, extraordinary landscape from above,” said Sorrel, carrying her young son on her back as we walked, who kept irrepressibly pointing out cygnets and baby mallards in the water at the edge of the meadows. As much as the thought of experiencing the Levels from on high appealed to me, seeing them as a buzzard or a peregrine might, an ancient, hand-crafted mosaic of fields, villages and grazing marsh riddled by narrow waterways that has been reclaimed from tidal saltmarsh since Roman times, I was fairly sure that my debit card wouldn’t stretch to a twirl in the sky and decided that getting as near as I could was the best way of coming to know this place.

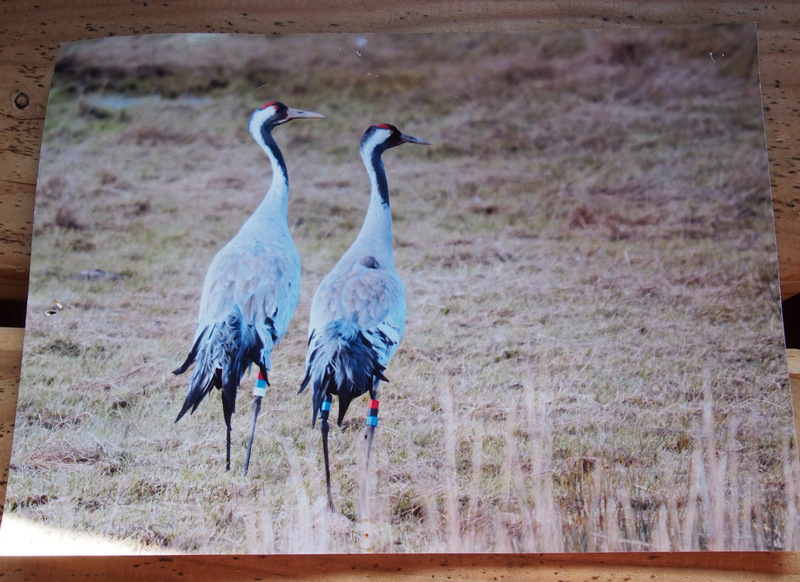

Besides, that practice of looking attentively and up close at things, whether through the lens of a microscope or simply by getting your hands dirty in search of the rich particularities of a place, has the weight of successful precedence behind it. It’s enabled scientists to establish the extraordinary ecological diversity and vitality of the Gwent Levels, home to an enviable range of species from the totemic otter to the rootless duckweed, Wolffia arrhizal, the world’s smallest flowering plant that’s found nowhere else in Wales, so tiny that you could hold thousands of them in your cupped hands. And it’s a technique that’s allowed archaeologists to painstakingly sift through alluvial silt to reveal boats from the Roman period buried miles inland or the astonishingly preserved Mesolithic footprints of the intertidal zone, the 7,500 year-old steps of adults and children off the coast, as well as those of various wild animals, including the common crane, a bird that until quite recently had been extinct as a breeding species in Britain for over 400 years. It’s a place that comes into clearer focus as you near.

But even at a distance the Levels are mesmeric, beguiling beneath wide, estuary skies. They shape-shift with the weather as you walk them, borrowing the magical sea-light of the Severn Estuary when it’s struck by sun, or turning as dark and dramatic as a storm-tide. By a set of lagoons near the coast, I watched a pair of those magical, rare cranes drop slowly through a bloom of late afternoon sunlight, lowering on vast open wings like they were descending by parachute, the glint of a scarlet crown on each of their graceful heads. For the past year this pair of cranes has been regularly crossing the Severn Estuary from a reintroduction project on the Somerset Levels, restoring the tie of antiquity between their species and the Levels landscape that’s been memorialised by those relic steps beneath the tide. There’s hope that in the future cranes will breed there again, and if they did they would join some of the other charismatic species that dwell on the Levels, such as avocets, little egrets and water voles. The water vole occupies an unenviable position in modern Britain; it’s the nation’s fastest declining wild mammal, its population having nose-dived by as much as 90% since the 1970s. For a period of nine whole years it had gone unseen on the Gwent Levels until a successful reintroduction scheme returned the mammal to its native home in 2012. From those small beginnings at Magor Marsh the water vole has spread over three miles on its own, journeying outwards across its former habitat by reen, like the ripples from a stone dropped suddenly into still water.

Reen, from the Welsh rhewyn, is the local word for the watery ditches that criss-cross the landscape like arteries, the primary feature of a complex drainage system that was dug over many centuries, and which included a subtle variety of components, from parallel field depressions known as ridge and furrow to shallow surface grooves called grips. On a map of the region the reens appear in bewildering blue numbers, like a dense grid of city streets, carrying water from the uplands and local springs safely out to sea in order to protect the reclaimed land from flooding. And it’s these earthen-banked ducts that set the Gwent Levels apart, making them both culturally and ecologically unique. Sculpted on top of an older Roman landscape of reclamation which was buried by alluvium some 1500 years ago after sea defences failed, the Levels reflect the long and evolving relationship between coastal people and the sea. Most of the present-day reens are medieval in origin, some of them the work of monks who lived and worshipped on the Levels. Such is the uniqueness of the historic, human-shaped landscape, including an evocative line of majestic old sallow trees that are believed to have sprouted from the willow mats laid down by monks attached to Tintern Abbey when crossing a particularly wet field to reach their grange farm near Magor Marsh, that the Gwent Levels are a designated cultural monument in Wales, a Landscape of Outstanding Historic Interest. And like those woven wands of willow that have sprouted into trees, culture and nature are deeply entwined across the landscape, giving rise to the wild diversity of the reens.

I sat in on a reen-dipping session with a class of schoolkids at Magor Marsh run by Kathy Barclay, an inspiring community education officer for the Gwent Wildlife Trust. It’s not only scientists and archaeologists who get up close to things, for it’s also the native and intuitive approach that children take to the natural world when given the opportunity. It’s how they’re able to engage with it so richly and perceptively, responding to creatures and sensations of all shapes and sizes with an equal degree of interest. I watched as the 9 and 10 year-olds scooped water, weeds and a wealth of aquatic creatures from the reen with enviable delight, scrutinising the plastic tubs where they’d sloshed the contents of their nets with rapt fascination. They pored over delicate ramshorn snails, tiny, flickering bloodworms, and the startlingly large beasts that are dragonfly nymphs. Racing back and forth with their dripping nets, hollering to each other about a particular discovery or laughing when someone returned with an arm wreathed in weeds, that small reen of their fascination and focus was nothing less than a world to them, which happens to be scientifically as well as imaginatively true.

“We have 144 Red Data Book aquatic invertebrate species across the Levels,” Sorrel had said when she handed me a net a couple of days earlier, encouraging me to go dipping for the first time since I was a child. “That’s the diversity and rarity that you’re looking at here, because each reen is subtly different. You get fast ones, slow ones, shaded ones, not so shaded ones, so you have this massive variety of reens which suits a massive variety of invertebrates.” Once I got started, I found it hard to stop, twirling my net through the water in a figure eight as Sorrel had suggested, peering into the tub at the treasure I’d hauled up. Looking closely at them, every single one of those myriad blue lines on the map is wholly unique, supporting a singular cast of aquatic organisms according to the reen’s physical characteristics, as if each waterway were a stage for a different play.

In hindsight, though, I wish I could have taken that helicopter ride after all, because there’s no better way of appreciating scale than from height. In recognition of the remarkable ecological richness of those reens, the Gwent Levels are listed as a suite of eight adjoining Sites of Special Scientific Interest, encompassing most of that beautiful, ancient place and supposedly safeguarding it against development. From above I’d have been able to see how that nearly seamless stretch of protected land on both sides of the River Usk reaches all the way to the estuary, a glittering green sweep threaded by living waterways and studded with church spires. And while I was up there, I’d have had a clear view of what 14 miles of motorway would look like when driven like a stake through its secluded heart.

Despite the protective measures in place to preserve them, the Welsh Labour government intends to lay six lanes of concrete and asphalt over the Gwent Levels, building a new section of the M4 to ease rush hour bottlenecks where the current motorway is pinched from three lanes to two in the Brynglass Tunnels north of Newport. Their chosen route -named the Black Route in proposals- would carve open four of those SSSIs and the Special Protection Area of the River Usk, as well as fragmenting the Landscape of Outstanding Historic Interest at a cost of at least one billion pounds to the taxpayer. The M4 relief road would irrevocably alter the unique character and integrity of the Levels, something that even the great flood of the Bristol Channel in 1607 (1606 in the Old Calendar), movingly commemorated by a high-water mark chiselled into the outer wall of the Church of St Thomas the Apostle in the village of Redwick, couldn’t manage, despite the terrible tally of death and destruction that those rising waters wrought.

The motorway would spell the end of the Levels as an intact repository of cultural and natural wealth. As the study for the characterisation of the Gwent Levels as a historic landscape makes clear, “the sum of the whole is greater than the sum of each part.” Along with the direct loss of habitat beneath the concrete footprint of the motorway, one of the largest single losses of SSSI land anywhere in the UK, the M4 bypass would rupture the essential cohesion of the place, acting as an impermeable barrier to all flightless wildlife, snapping protected habitat like a cracker in two, and isolating wild animal populations on either side of the divide. “It seems ironic,” said Kathy Barclay, “that we’re reintroducing water voles and re-establishing a population that’s going to be cut in half. Nothing’s going to go beyond the motorway.” While little wildlife will travel beyond the looming barrier once construction has begun, it’s likely that the effects of the motorway will seep everywhere, as each of the unique reens is coupled to another, linking up in a vast, interconnected drainage system that takes water southwards to the estuary. Any pollution from the motorway that enters one of the reens –whether from noxious fumes or a hazardous spill- would likely enter them all, carried along like disease in a bloodstream, fouling each of those singular, underwater worlds that the extraordinarily sensitive invertebrates are entirely dependent upon.

The Welsh government’s own website admits that during its consultation process it received more comments against the motorway proposal than for it, but dismisses them without a trace of irony as possibly being “the result of interest groups’ initiatives” while simultaneously championing the support they’ve received from corporate business. Even the Federation of Small Businesses in Wales has come out against the project, arguing that there are far better ways of spending such a colossal amount of money to develop the economy of south-east Wales. And despite its so-called need, no one I spoke to was in favour of a motorway across the Levels. Not bikers or birdwatchers, publicans or soldiers. Not even the taxi driver from Newport or the lorry driver from Port Talbot that I imagined might have more sympathy for the development in light of their working lives. Regardless of whether the people I spoke to lived on the Levels or elsewhere in Wales -and many of them regularly used the notorious M4 tunnels- they all articulated the same point of view, a deep concern about the project’s vast cost at a time when local services were being cut and a passionate belief that the place should be preserved as it is, just like it was meant to be, for its wildlife, historical importance and open character.

“It’s hard to believe what these fields once were, and what they still are. When the tide comes in you get a real sense of their history.” I’d stopped for a coffee one afternoon at a café near the village of Goldcliff after seeing Wayne Mumford, the owner, standing on a picnic table while trying to photograph baby starlings in the eaves. “When I think that the Romans and the monks built this area where there’s so much history, and all the life that lives in the reens, I can’t understand why anyone would want to build a motorway through the Levels.” Wayne had shaken his head in the same dismayed way that Lisa Morgan had inside Donnie’s Coffee Shop in Magor where she’d been helping out the day before, though her voice was sharpened with anger and frustration: “I have to drive into Newport about five times a week and does the current motorway bother me? No. If I have to wait a little longer does it bother me? No.” She went back to wiping the countertop before continuing. “The sad thing is that politicians think they can ride roughshod over people and if they take a little bit, generally they’ll take a little bit more and the core of the place will have already been eaten into. And once it’s gone, we can never have it back again.”

What’s at stake with the Welsh government’s plan is not solely the unique and irreplaceable environment of the Gwent Levels, but the kind of future we wish to leave as our legacy. Do we honour protective measures for the purpose they were intended, leaving intact those places of natural and cultural significance, places that are necessary for both wildlife and our own well-being, or do we dismiss them as irrelevant, narrowing our focus until it excludes all but a relentless fixation on development at any cost, corroding the wider duty of care we’ve been entrusted with? In 2015 the Welsh government passed the Well-being of Future Generations Act, a bill that explicitly highlights sustainable development as the key to “improving the social, economic, environmental and cultural well-being of Wales.” When such gems as the Gwent Levels can be sacrificed for the sake of development, it reveals just how empty of meaning the concept of sustainability can be. “We have to think outside the box as it were,” said Kathy Barclay as we sat in the nature reserve office. “We need to think of different solutions. The history of this place, and the cultural aspects of it are irreplaceable, so once you’ve wrecked it it’s gone. It’s absolutely gone.”

The Future Generations Act also obliges public bodies “to make sure that when making their decisions they take into account the impact they could have on people living their lives in Wales in the future.” After the schoolkids had finished reen-dipping, I walked back through the meadows towards the classroom with them. They carried a small selection of creatures in glass jars to look at under the microscope, to bring that captivating world beneath the surface of the water into even greater focus. As swallows curled through the dry summer air and dragonflies glittered over the meadow grasses, I asked a number of them what it was that they enjoyed about coming to Magor Marsh and the Gwent Levels. Each and every one of them, spoken to individually, gave me the same two reasons, as though they weren’t answering a question, with a range and diversity of possible responses, but had instead drawn on a well of common sense in kids. Firstly, they adored the wildlife – all the myriad bugs and birds and butterflies that they got close to on each visit, the very things that accord the Levels their celebrated, scientific designations. But secondly, and of greater surprise to me, they all said they loved the peace and quiet there, the silence away from home and school. That silence must be a strange and phantom thing for them: having already recognised its importance in their young lives, they’re witnessing its increasing disappearance from their experience, the same silence that would be lost alongside the wildlife they loved from large parts of the Levels with six lanes of cars, coaches and lorries roaring through it. Another piece of the place chipped away, leaving a lesser sum in its stead.

In many respects the children that morning had been much like I’d imagined, a group of ordinary boys and girls who were simultaneously excited, noisy, curious, polite, pushing and laughing, and it was clear that this future generation already had an important stake in this present place, a set of emotional and imaginative connections that immeasurably enriched their lives, highlighting the enlightened reasons why landscapes like the Gwent Levels were originally protected. These were the citizens the well-being act was intended for, those who would inherit our decisions, who would grow up in a world diminished by the loss of unique places if we’re to sanction their destruction. As we crossed a bridge over the last reen before reaching the nature reserve classroom, the kids abruptly stopped talking and watched the water instead. That sudden, overwhelming hush of wonder when they saw a water vole swim across the reen could yet be the sound of nature’s future, and hopefully an enduring element of their own.

This is an early version of a chapter on the Gwent Levels that features in my new book, Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save our Wild Places.

Wonderful, Julian. So clearly an area of irreplaceable wonder but yet so clearly symptomatic of a world in which business and development – often regardless of local wishes – are the only game in town.

Many thanks, Steve. I was really struck by the number of local people, or those from farther afield, who were against the project, most of whom felt they had little power to alter the course of events around them.

I so enjoyed these glimpses into this mesmerizing corner of our world. Thank you. As ever, you write like a dream.

Thanks ever so much for your generous compliment, Jean. Especially coming from a writer whose work I admire so much. Hope you’re well!

a microscope, a helicopter or a child I would add.

I absolutely agree!

Another fascinating read! I so dearly hope that this beautiful area will be preserved and protected for future generations as well as our own sake.

Thank you, Verena. I very much hope your it’s saved as well; few places have resonated so magically with me in recent years. Thanks for reading and hope you’re well!

” Wolffia arrhizal, the world’s smallest flowering plant that’s found nowhere else in Wales, so tiny that you could hold thousands of them in your cupped hands.”

Excellent post, Julian! And more power to the elbow of conservation and reason!

Cheers

Charles

Thanks for your good words, Charles. “Conservation and reason” – excellent summation of what we could do with having a lot more of in this world! Hope you’re well!

words fail me (often) Julian, but thankfully they do not fail you. I am on tenterhooks now to read about LH.

Many thanks, Miles. Will hopefully be turning my attention to the Lodge Hill chapter and nightingales sometime this winter. Another gem of a place, and very fond memories of our visit.

Excellent post on a subject about which I knew nothing. Signed the petition and will try to visit the levels when next I am in the area.

Thanks kindly for taking the time to read and sign the petition, Julian. Much appreciated, and I hope you enjoy your visit to the magical Levels whenever you get a chance. Best wishes from here.

I have never visited the levels but you capture the myriad facets of what must be such a precious landscape area and cultural resource. It also struck me how we have to fight not only for the landscape but for language itself. When designated ‘Landscapes of Outstanding Historic Interest’ and SSI sites can be seriously threatened by Motorway Relief Roads to ease traffic. Concepts such as Future Generations Acts are hollow lip-service when this short-term madness is even contemplated. Thanks for drawing attention to this Julian and the beautiful writing as always.

Many thanks, as always, for your kind words, Fifepsy. I absolutely agree with you about fighting for the language as well as the landscape. It’s such a relevant point that you raise; what meaning does protection of any kind have anymore when it can so easily be overturned without much standing in the way of it? We saw it with Trump’s golf course in Scotland, and we could yet see it on the Gwent Levels of Wales and England’s Hoo Peninsula. As admirable as the language and aspiration of the Future Generations Act is, it’s utterly meaningless without a corresponding intention to honour the protective measures and values that make these places so significant.

Excellent piece Julian.

Many thanks, Daniel; much appreciated.

Hello Julian. I finished your post feeling enchanted by this place and, in equal measure, furious with what is being proposed for its future. What poverty of imagination there is among our political rulers!. Apropos the recent spat between Mark Cocker and Robert Macfarlane, I think you have shown here why writing of this sort is an essential component of our attempt to care for – and about – the natural world. If the argument can be made with words so beautifully woven together as those in your post, then there is a greater likelihood that people will take the time to listen and reflect. Thank you. Looking forward immensely to the new book.

All the best from Catalonia

Dear Alan, many apologies for the late reply. For some reason I’d missed this wonderful, and extremely generous, comment of yours. Like you, I had a similar set of feelings while walking the Levels in June: equally enchanted by an extraordinarily rich and layered place and dismayed at its possible future. We clearly seem to have reached a point where protective measures mean little anymore, and we’re faced with the enormous question of what is important in our landscapes and experience. I set out to research this book knowing that I’d have to face up to a lot of grief, but it’s the remarkable people that I’ve met of all ages and walks of life who’ve given me hope as they dig in each day to protect the places they love. It’s been a joyous journey in many respects, coming to know some of the vibrant connections that people keep forging with places, but it’s a joy that’s underpinned by a serious fear for all that might be lost in our lifetimes, let alone beyond them. Many thanks for your kind words and thoughts; I really appreciate them. Best wishes from Prespa, Julian

Oh good luck in your campaign. What a wonderful piece you have written. This following is what I sent to the Welsh Assembly: “Although I live in England (Devon), I travel the M4 to and from West Wales – where I did my PhD reseach on the Red-billed chough in order to re-establish it in England (Cornwall) – and I am horrified at this proposal. What’s a bit of inconvenience compared to a pristine jewel? I’m ashamed that it’s Labour proposing this. Tell Jeremy!!” I mean Mr Corbyn of course.

Thanks ever so much for your kind words; delighted you enjoyed the writing! Terrific comment you’ve sent along to the Welsh Assembly. It really is a jewel as you say, and it would be an incomprehensible loss if it were let go. Thanks for taking the time to read, much appreciated.

The amount of response you’ve had and are still getting indicates just how important this is. Sadly the same kind of thing is happening all over the place; HS2 massively for example. Thew best of luck in your campaign, Good wishes, Dr Richard Meyer.

You’re absolutely right, Richard. Rarely a day passes when I don’t learn of some place or other under threat which people are attempting to preserve – for its wildlife, history and their deep and meaningful connections to it. I may well look at HS2 for the book as well; in truth you could write umpteen volumes about this issue which is so critical at the moment. Thanks very much for your good wishes; one thing I’ve learned from researching this so far is discovering the sheer number of wonderful people out there trying to make a difference. It feels like the bright light in the distance. Best wishes, Julian

I agree, what an excellent piece here!

Thanks ever so much, Stuart – much appreciated!

What an amazing photo!

Thank you!

Reblogged this on bulukumbamemilih.

I love this post!

Many thanks; much appreciated!

Superb article of great interest

Thank you very much; I’m delighted you enjoyed it.

Good

Thanks!

Wow Julian, i am absolutely mesmerized with this place…and the way u described it; it was as though i was in that very place experiencing like an adventure

Thank you so much for the wonderful read

Thanks ever so much for your very kind and generous words, jinxoak. It really is a magical place so I’m delighted that the post resonated with you. Thanks for taking the time to read; much appreciated!

Amazing photos. They look so clear.

Many thanks – delighted you enjoyed them!

You’re welcome, you deserve it :)

Nice pics

Thank you!

This is such a fascinating place..beautiful images taken..long live the Gwent levels.. Thanxx for sharing this..:)

Thanks ever so much for your kind words; they’re much appreciated :) I agree, long live the Gwent Levels!

Reblogged this on My Blog.

This so picturesque!! Wish even I’d visit it sometime. But anyway you’ve brought out the beauty in the best way!

Many thanks for your generous words; I hope you get a chance to visit the area some day!

Nice

Thanks!

Nice pics

Thank you!

Awesome!!!

Many thanks!

Brilliant post and a great use of images to get your point across. The area looks beautiful and regardless of how you view it, I reckon it is a spectacle.

Didn’t know anything about the area until I read this post. Will definitely be somewhere I will consider visiting on my travels.

Thanks ever so much, Dan. The whole area contains such a wealth of diversity that a visit would definitely be worthwhile. I spent four days there and rarely a moment passed that I didn’t discover something of interest. Thanks for taking the time to read; much appreciated!

Your blog is simply wonderful julian.

I want u to have a sneak peak at my blog “This is what I want”

Its my first blog.

Delighted you enjoyed it, and many thanks for the kind words.

Amazing :)

Many thanks!

This seems like a photographers paradise. Endless amounts of beauty followed by historical context’s, you couldn’t ask for a better post then that of which you posted. I was truly in awe while reading this and want to thank you as well for posting such a piece. I am definitely following you from now on.

Many thanks for the wonderful and generous comment, Nick. It really is a wonderful place where at any moment there seems to be something new and interesting to photograph, from wide vistas to close-up nature. Hope you get the chance to visit sometime. Thanks again and best wishes, Julian

nice post

Thanks!

Sígueme y te sigo 😊

Lovely writing on a beautiful, important subject. I’ve also learned about an entirely new place today! Thank you.

Thanks ever so much for your generous words; so pleased the post resonated with you and many thanks for taking the time to read! Best wishes, Julian

amazing! love your words

Many thanks for your kind comment; delighted you enjoyed the post!

Reblogged this on Người Đến Từ Bình Dương and commented:

Thank you.

Many thanks!

Beautiful images and lovely text about the interactions of humans and the landscape. You’re so right that we can’t spare any more wild space for asphalt. Good luck in the campaign.

Thanks ever so much for your generous words. It’s those interactions that you mention that makes these places so meaningful and memorable. Hopefully wiser heads will prevail and preserve this one for those deep connections.

Very Beautiful Images of Gwent Levels Thank You For Your Post

Thank you very much; I’m so pleased you enjoyed the post and images.

Reblogged this on psychosputnik.

Nice

Thanks!

That was great so..

Reblogged this on wtcbank.

Gorgeous place! Thank you for the thoughtful tour:).

You’re very welcome; thanks for taking the time to read, much appreciated!

It looks amazing I wish I could go there!!!😀😃😆😄

Well worth a visit if you ever get the chance!

I love this!

Thanks very much!

Reblogged this on koksian.

oh how I love nature, what can I say Absolutely Beautiful.

Many thanks for the kind words!

Reblogged this on amahichavez and commented:

me gusta este paisaje<3

I wish I have this beauty to photograph

Beautiful !!!!

Thanks!

Really enjoyed reading the blog and the looking at the photographs. Great job.

Thanks very much for your kind words, Nikita. I’m delighted you enjoyed the post!

Reblogged this on Mon site officiel / My official website.

Nice photography!

Thank you – so pleased you enjoyed it!

Absolutely enchanting article! Some of the photos are inspirational, too. Keep it up :) I’ll love to read more soon.

Thanks ever so much, CJ – delighted you enjoyed the post!

It’s wonderful. Si quieren un blog genial sobre cuentos e historias, aquí les dejo uno https://dearwalkirya.wordpress.com/

Thank you!

Great interesting blog! I would love to see more of it. Keep on writing :)

Thank you very much, Kally; much appreciated!

You’re most welcome

nice

That’s amazing

Thank you!

Wonderful insight to a wonderful area,thank you for mentioning Seawall Tearooms and hope you will visit us again

Dear Wayne and Wendy – it was an enormous pleasure to meet with you both that day in June. Thanks ever so much for the hospitality and will definitely drop by when I’m next on the beautiful Gwent Levels!

Breathtaking views! I respect you for bringing awareness about a subject of such importantce!

Thank you, Calina. I’m so pleased you enjoyed the post and appreciate your kind words.

Reblogged this on nadinekarkour's Blog.

Beautifully written as ever Julian. Petition signed.

Thanks ever so much, Mark. That’s kind of you to say, and thanks for signing the petition.

Enchanted! Felt heavenly! Julian!

Thank you very much, Soundarya!

Good

Thanks!

It is the right time, stand up and shout, turn up the heat on our government, and save our wetlands.

You’re absolutely right, Bob. There’s so much at stake these days. Many thanks for taking the time to read and comment. I appreciate it, and hope these voices of resistance are heard.

Great article, thank you!

Thanks ever so much; so pleased you enjoyed it!

What a beautiful sense of place in sensitive writing and photographs. Thank you. I am nearly blind, but this makes me see again.

Steve, I think these are the most moving words I’ve ever heard about my work. I’m deeply honoured, and touched that the piece resonated in this way. Thank you ever so much. Best wishes, Julian

I love the fact that the children referenced the land’s quietness as one of the things they enjoyed most about being there. I also admire the way your writing imbues scientific information with a magical feeling. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks ever so much for your kind words, Emily. I was so surprised when the children mentioned the quiet; it was probably the last thing I expected them to say in fact. Maybe our concerns about children spending too much time in front of glowing, moving screens should be refocused to give them greater opportunities to be outside in a natural environment. Perhaps we’re looking at the issue from the wrong angle. Their connection to the place, and all it offered, was deeply moving. Delighted you enjoyed the post, and thanks for taking the time to read. Much appreciated!

Reblogged this on jmacarpio.

Good job

Many thanks!

Reblogged this on Kania-Info .

Agree completely about giving children back the freedom to roam. They are the future and creating a world they can inhabit should be our highest priority.

Perfectly said about children and their future. Many thanks for taking the time to read.

My first ever post used childhood exploration as a kind of mission statement –

“My voyage of exploration begins. I want to recapture the spirit of childhood, when we would set out from home with the deliberate aim of getting hopelessly lost. No point in going over old ground, after all …”

Since then every post has touched on freedom, in some way – music, personal influences, etc. If interested, see https://davekingsbury.wordpress.com

I very much enjoyed having a look at your blog this morning, Dave. These sentences of yours beautifully capture that necessary spirit of curiosity and inquisitiveness that guides children to such rich, and often unexpected, encounters with the world. It’s a good path to be on, I’d say. Best wishes, Julian

Thanks, will continue to follow your beautiful blog – ugly word, blog, wish I knew of another!

Wonderful post about as wonderful place. Very important it is preserved for future generations. FYI the great flood of 1606 was a tsunami, caused by an earthquake under the Irish Sea. Swept up the Bristol channel, Bristol itself was under about 8 feet of water. Incredible.

Many thanks for your kind and generous comments about the post, Barb. It really is a remarkable place that will hopefully be preserved. I’d been reading about the tsunami while in the Gwent Levels area, and seeing the landscape afterwards brought quickly to mind how shocking it must have been. Thanks again!

Reblogged this on photography by julioc.

Wonderful pictures. Truly amazing !

Thank you!

You write so well madam. Great pictures too. Followed!

Thank you very much – so pleased you enjoyed the post and thanks for reading!

Thanks

Much appreciated!

love it..great pics and concept

Many thanks – much appreciated!

Good images!

Beautiful article about a beautiful place. Final call for Formal Objections to the Motorway is today (4th May 2016). Do please consider responding. The RSPB e-activist site helps you respond: http://tinyurl.com/lovethelevels

I like the flowers in first photo

A wonderful article about a unique part of our countryside that I remember from my childhood when my father used to take the family out in the car. The reens were where I first found frogbit, which I was pleased to see in one of your photos. To my mind it is unthinkable that somewhere like this is threatened with destruction. As a boy, I used to think places like this and the amazing wildlife they supported, would be here for ever, but sadly all through my life I have been watching the countryside being destroyed and once common flowers and animals becoming rare, with others threatened with extinction!