I first met Matina Galati in a grove of extraordinary juniper trees on a limestone mountain above the Prespa lakes where I live in northern Greece. That day, I’d been walking with the Hungarian gardener and botanist Máté Tálas and two friends of his when Matina arrived from Athens to join the group for the rest of their trip. She and Máté had worked together in the Mediterranean garden of Sparoza outside of Athens and shared a keen interest in exploring the landscapes and plants of the wider Balkans. While we ate a picnic lunch together in the juniper grove, where several of the ancient trees had taken on unusual and impressive shapes over the centuries in response to fires and storms and snow, Matina told me a little about her work as a gardener and illustrator at Sparoza, where she sometimes hosted workshops in botanical painting, before I eventually said goodbye to the group and let them continue on their journey.

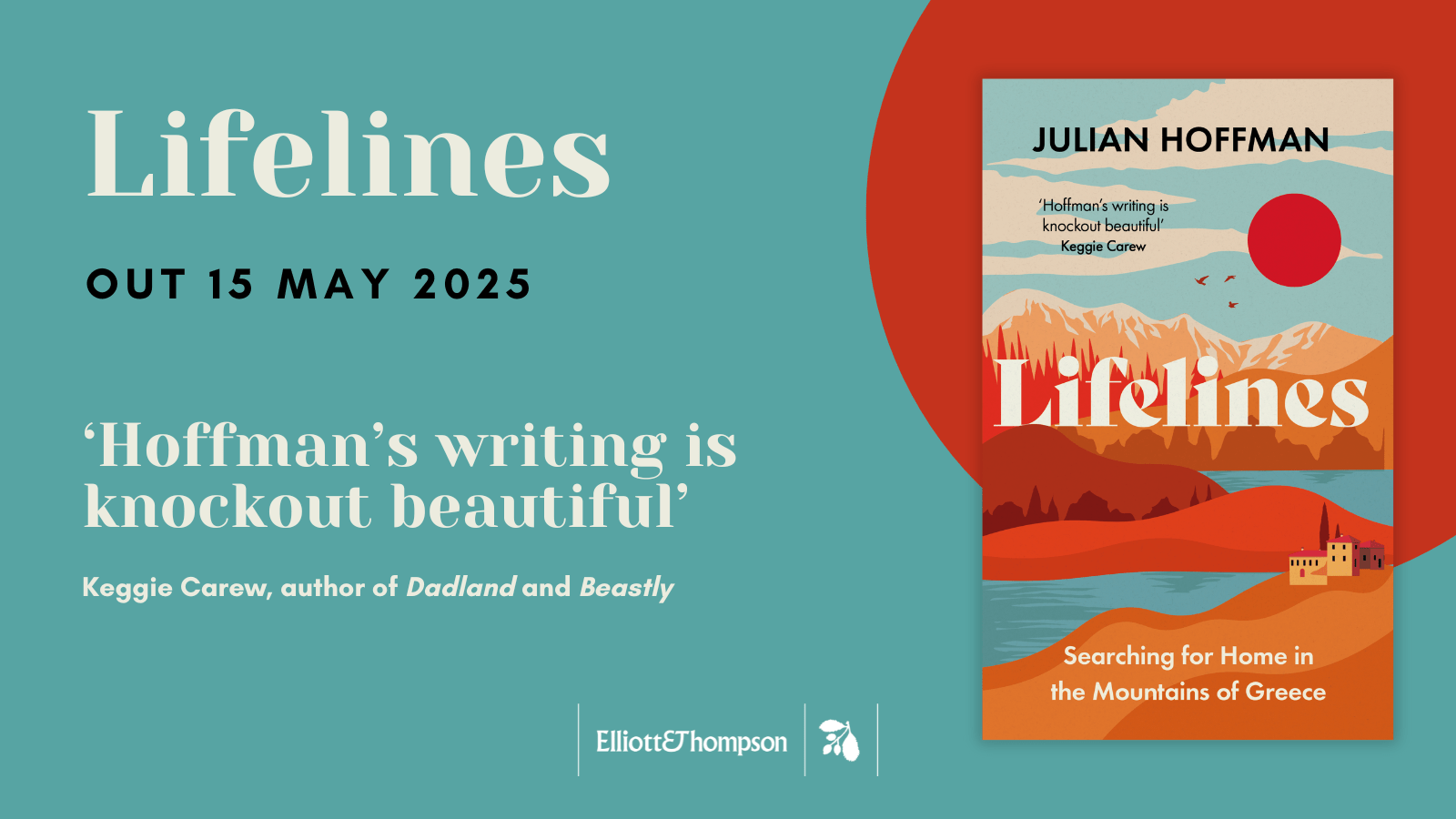

It was only afterwards, when I discovered Matina’s work online, that I was able to appreciate the beauty of her illustrations. How her striking use of colour highlighted the elegant perceptual precision of her sketches, where light itself seemed to be used as if a brush. Later still, she would share with me some remarkable illustrations for a children’s book she was working on, inspired by the Dadia Forest after wildfires devastated so much of that irreplaceable national park in northeastern Greece. Not only did her paintings hold an entrancing grace but they displayed an enormous empathy for other species, telescoping in on their joint resilience and vulnerability. As soon as I saw them, I knew that I wanted to ask Matina if she would consider creating the interior illustrations and a map of the Prespa basin to go with the beautiful cover design by Ola Galewicz for my new book, Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece.

Julian: Firstly, I would just like to say how thrilled I am that you were so enthusiastic about this project right from the very beginning, Matina. And it seems so fitting that we first met in the juniper grove that ended up playing such a large role in my book. What were your first impressions of this place, as I think it was the only time you’ve been to Prespa? And how did those impressions and experiences shape your ideas for the map and illustrations?

Matina: I remember that day vividly. I had taken the long road through the mountains by accident, instead of the highway. As I was driving through the winding mountain roads covered in fog, I discovered a landscape I had never experienced before, as I come from a different part of Greece. When I eventually arrived, I was very late and I had missed most of the hike, so I found you and the rest of the group at the juniper grove. The trees felt enormous and ancient. The whole place had a hypnotizing quality to it. In your book, you describe the juniper grove as a room. It absolutely felt like that, being surrounded by these trees and immersed in their presence.

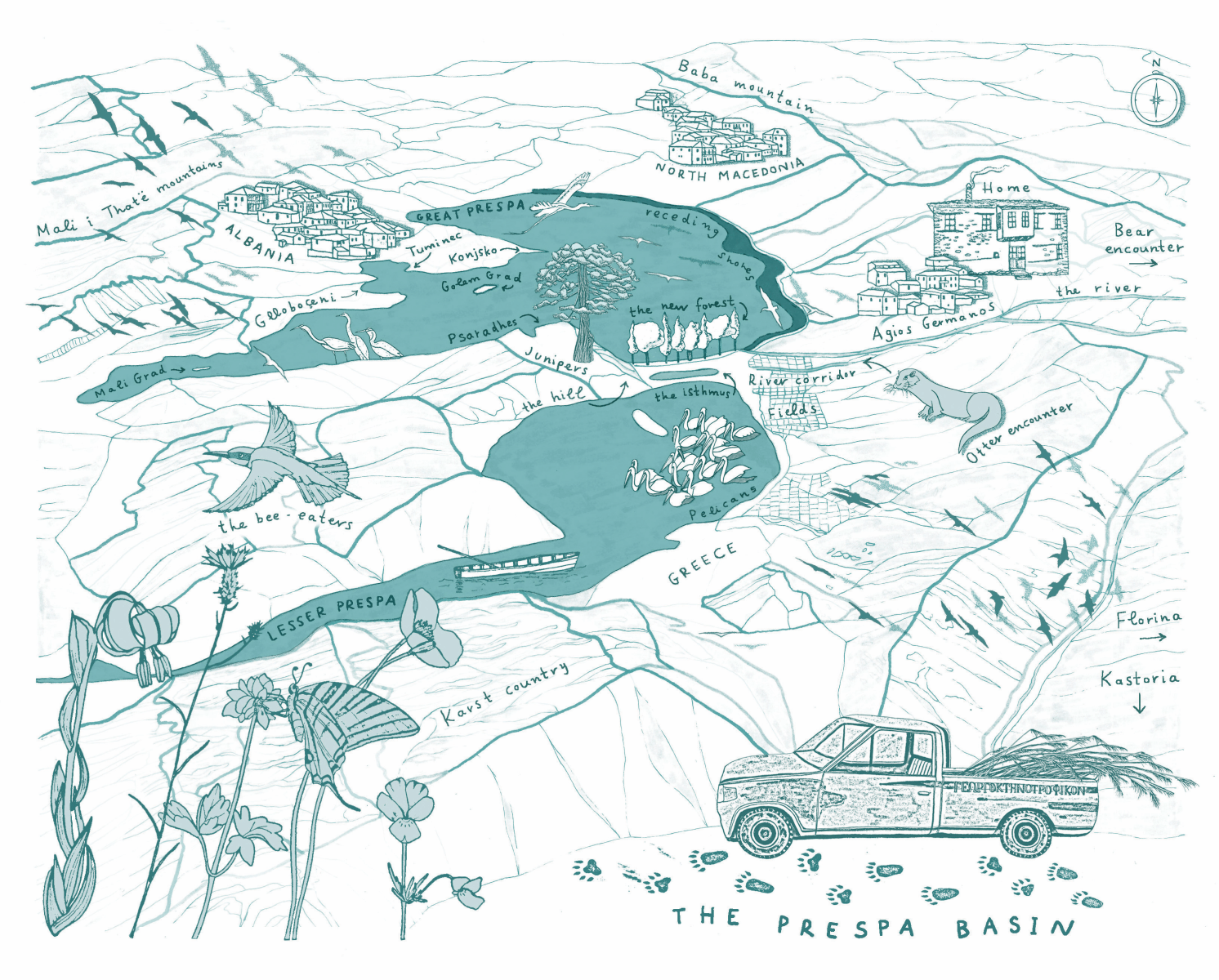

Afterwards, we climbed down to research the plant communities of the area surrounding the lake. There, I saw for the first time the pelicans flying in the sky above. It struck me then and there that this place was a home shared by plants, trees, birds and humans alike. I wanted for the map to reflect that and for the illustrations to convey intuitive observations of all these elements.

Julian: You trained as a landscape architect and have since gone on to work in various botanical gardens. Was that a natural transition for you? Because one of the many things that I admire about your work is the meticulousness of your illustrations, especially when it comes to plants. But it’s an imaginative meticulousness, in the sense that it feels like you’ve taken the ideas of classical botanical illustration in field guides and given them a chance to breathe through a vibrant combination of colour and movement.

Matina: I realized quite early on, that designing just for the sake of it was not for me. From my early years as a student, my interests started showing and it was becoming obvious that I was not going to follow a conventional path in architecture. I was more interested in being outside, studying places and what makes them what they are. And of course, listening to the stories these places were telling me and then, based on their footing, building my own.

I saw plants as one vital element of a story that I didn’t yet know. So, I decided to work as a gardener to try to understand and learn as much as possible. With my background in architecture, it was difficult to get accepted for such jobs: my training wasn’t in agriculture or biology, and for a while, it seemed that all doors were closed. The current world has a knack for commodifying our talents and putting us in a box. You can only be an artist or a botanist or an architect. Why can’t I be all of them at once?

I am still working on combining all my areas of interest, which I see as interconnected, into one practice: art, design, conservation, research and preservation of cultural heritage. My illustrations are the result of this path I have followed.

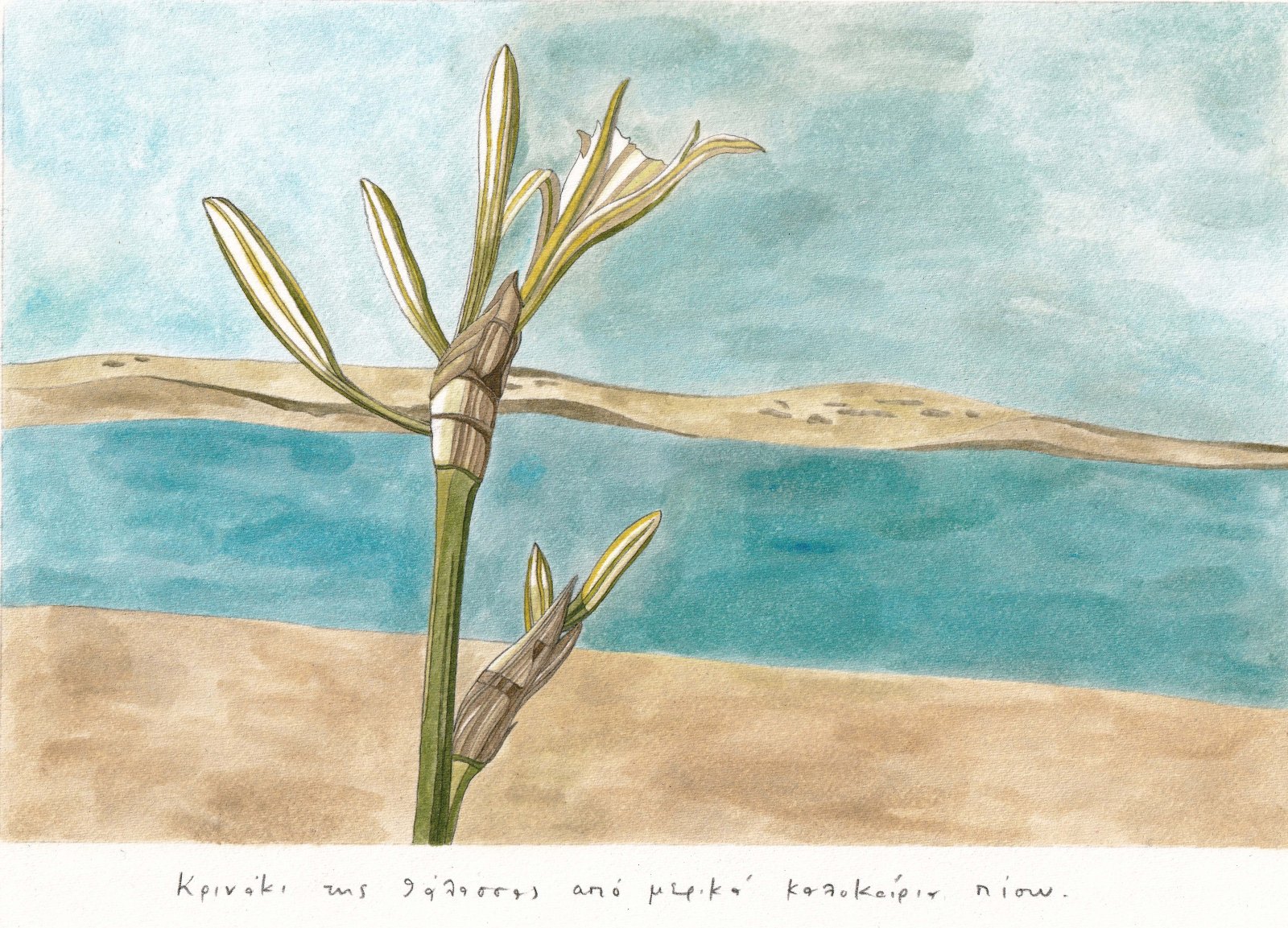

Julian: Although you now live between Athens and Amsterdam, you’re originally from an island village. Does that landscape still influence you as an artist? I’m particularly interested in your use of light – not only in your paintings but in your photography too, which has a wonderful glow to it – and how it often seems to me to reflect that distinctive light of the Greek islands?

Matina: I come from a farmer’s family, so working the land is built in my memory. The unbroken ties with the countryside are a characteristic of my heritage, even if most of my generation lives in densely urbanized city centres. Looking back to the summers I spent on the island, I remember my grandparents working the χωράφι (land) and an all-encompassing warmth coming from the scorching sun. I came to understand colour in relation to light and temperature. I think that the way light is conveyed in my painting or my photography is directly related to memory and lived experience.

Julian: I remember you saying to me while you were working on these illustrations that you found the work to be a real challenge because you tended to think of colour as being at the core of your artistic practice? How did you approach these illustrations knowing that colour, for printing reasons, wasn’t an option, other than being able to use a single colour for the map on the endpapers?

Matina: Knowing from the start that full colour illustrations weren’t an option in our case, I shifted my focus elsewhere. For the map, I aimed to highlight the topography and the interaction of the characters within it and its various landmarks. For the illustrations, composition played a vital role, as well as communicating certain concepts that are prevalent themes in your book. The result, I like to believe, are tender portraits of all these elements: the co-existence of the two primary juniper species in the juniper grove (Juniperus excelsa and Juniperus foetidissima), the entangled positioning of the bee-eaters on the branch of a wild almond tree, conveying the shifting of the seasons and, finally, the Dalmatian pelican resting on the fisherman’s boat, signifying the shared nature of this landscape.

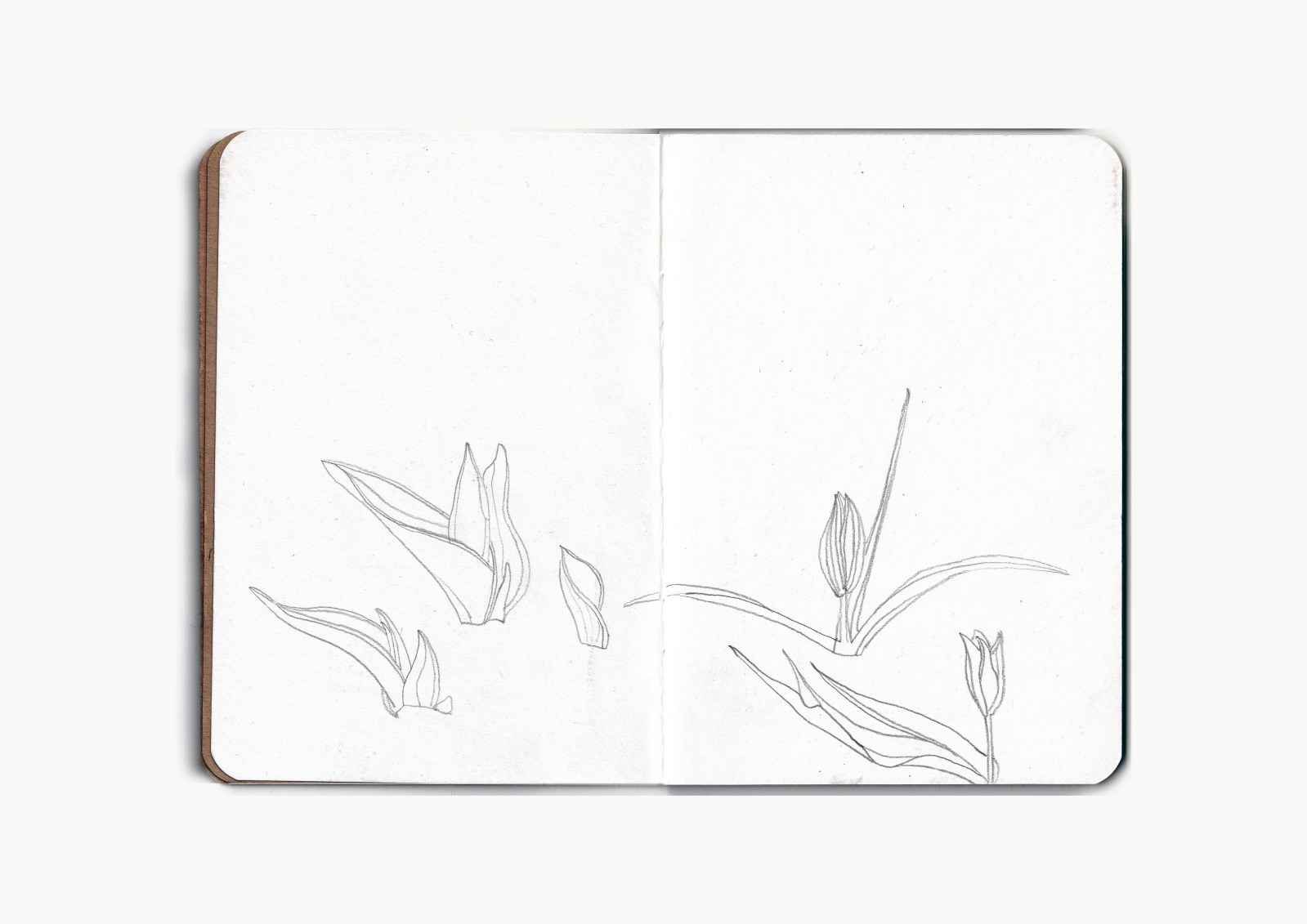

Julian: Can you tell me a little about your process in the field? I know you’re a big fan of working with notebooks and that you’ve often hosted painting workshops at botanical gardens to encourage others to illustrate plants, so I’d like to know what’s key to your practice? And how important it is for you to know the species that you’re illustrating?

Matina: I feel like because of my education, I am always working on the threshold between science and art, something that is a blessing but also a place that’s difficult to navigate at times in order to distil my voice clearly and find the balance that feels right. In the past, I have felt that maybe my more “rigid” training as an architect was taking over and suppressing my more playful side. That is when I started carrying sketchbooks to draw and write down quickly my observations and ideas as they came. I like to draw outside so that my drawings retain their vividness and spontaneity and then take them home to paint, which is a slower, more introspective process. I draw most of my inspiration from the actual species and I think that what I do with my illustrations is mostly interacting with what is already there. The inspiration in my work comes from the subject matter, from an outside source and not me. Painting nature is so forgiving, I honestly believe there is no such thing as a bad drawing of a plant. This is what I try to instill in those who come to my painting workshops. It truly is more about cultivating seeing and understanding.

Julian: One of the things that I love about the map that you created for the book is the absence of borders. The names of the three countries that share the Prespa watershed are clearly there – Greece, Albania and North Macedonia – but the dividing lines are missing. Can you tell me about that decision and why you felt it was important to leave the lines off the map, even though the three countries that come together around the water are still visible?

Matina: This was, for me, one of the most significant parts of our collaboration, and I am so glad we saw eye to eye on this. This is an idea that you touch on brilliantly in your book as well, which is that landscape knows no borders. The rocks, the bears, the birds and all the beings that share the landscape of Prespa exist and move freely on either side of the borders. When we stood on top of the hillside the day we met and gazed at the lake, it would be difficult to imagine it divided by lines. Only humans feel the need to divide each other with lines on a map. So, while it would be visually odd as well, it was also a deliberate choice to leave those lines out. I say this when recently in the name of borders, more than 500 people lost their lives during the Pylos shipwreck. All borders imply the violence of their enforcement. Your book, on the other hand, is about meaningful entwinement and co-existence.

Julian: I wanted to ask you about the idea of home. It’s one of the major themes of the book and it’s something that I think we’ve both wrestled with at times. What makes a place home for you? Either at the personal level or the broader context of our relationships with the world?

Matina: Something that stayed with me while reading your book was your idea that home could be an action, a verb, “to home”. I do believe that we have the capacity to create the feeling of home, through building and being surrounded by our community, through acts of meaningful solidarity and collective care. For you and your family, it was a conscious choice to search for home in another place, because you didn’t find resonance in your previous circumstances; I am especially fond of the photo of your wife Julia and you and the truck you used to drive, to carry the cut reeds you found near the lake, making your way to home.

At the same time, home is also the story I am about to tell you. I recently took my grandmother to see the olive trees she had worked on her whole life. She can’t visit them as frequently anymore and when I visited, she asked me to take her to see them. While we were walking through the olive grove, she took a branch in her hand and kissed the olives it was carrying. I can’t help but place this story in relation to what is happening to Palestine right now, where the occupation is uprooting lives and olive trees, in a futile attempt to forcibly erase home from a people’s minds and hearts. It is undeniable at this point that all life is being targeted in Palestine.

Julian: Finally, one of the things that you and I have talked about is loss in the natural world and ecological grief. How do we deal, at a psychological level, with the devastating damage caused by climate change and wildfires, for example, here in Greece. Is it possible to properly honour such grief? And if so, how, both personally and collectively, do we do that, knowing that there’s yet more grief on the way? And what role, if any, might art and stories have to play in that process?

Matina: I struggle with this, especially because the speed that we are currently losing things has become unfathomable, be it loss of the natural world or our own humanity. We have to take into account, if we are talking about Greece, that the political direction of the country is prioritizing entirely different things, such as tourism, the military etc. The priorities are all distorted and the conversation currently being had on the topic is ill-informed and irrelevant at best: greenwashing, dubious investments on “treatment” measures, an assortment of temporary solutions that treat the aftermath and not the problem. Our grandmothers’ knowledge is being lost, we are becoming more and more distanced from how the natural world works, to the point that, in the future, it might even become impossible to act, because we won’t know how to. For example, in Dadia, that you mentioned in your introduction, the farmers were playing a vital role in the protection of the forest. Their controlled, low burning fires revitalized the forest’s undergrowth and prevented the occurrence of larger wildfires; the grazing of their animals kept the forest floor tidy and its passages clean, making it easier to intervene in case a fire broke out; and their plough freshened the earth so that they could also build their lives in the fertile plains. This symbiotic relationship had kept the forest ecosystem healthy and alive for centuries. Dadia is just one example, but this is the case for many ecosystems and habitats in Greece and worldwide.

Here is where stories might come to play their most important role. I believe we need to document as many stories as possible, through art and with every other means necessary; not only to archive them and preserve their knowledge, but also to uplift them and make them the centre of our conversations. Only then will we properly honour grief, when these stories are heard and help shape our collective course.

I’m honoured to have Matina’s illustrations grace the pages of Lifelines – and they will also be appearing in the North American edition of the book that will be published by Godine in spring 2026. To find out more about her wonderful work please see her website here. Finally, I’m thrilled to say that there will be a special offer from my brilliant publisher Elliott & Thompson and participating UK independent bookshops, in which an A4-sized print of Matina’s beautiful illustration of bee-eaters (see above) on hammered paper will be given away with early copies of the book. More details about Lifelines, together with ordering information, can be found here. Thanks for reading!

Discover more from Julian Hoffman

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m keenly anticipating reading your new book next spring and am also looking forward to seeing Matina’s illustrations!